Ah-monds

California is home to virtually all of the world's Almond producers (California produces at least 80% of the almonds on the planet- last year that was 2.1 billion tons). As it turns out, most of us say Almond wrong. Here, they aren't Almonds, they's Amonds. Why? Well, as the local saying goes- to harvest almonds, you need to "shake the L out of them!"

Watch this video and see just how much of a shake these tiny trees get each Autumn (note the appropriate music choice- 'shake it, shake it, Cali')

California is home to virtually all of the world's Almond producers (California produces at least 80% of the almonds on the planet- last year that was 2.1 billion tons). As it turns out, most of us say Almond wrong. Here, they aren't Almonds, they's Amonds. Why? Well, as the local saying goes- to harvest almonds, you need to "shake the L out of them!"

Watch this video and see just how much of a shake these tiny trees get each Autumn (note the appropriate music choice- 'shake it, shake it, Cali')

Almond bloom near Chico. Photo by Art Siegel

Almond bloom near Chico. Photo by Art Siegel Last week, at a pollination workshop hosted by the UC Agricultural Extension office in Woodland, California, I learned a lot about both honey bees and native pollinators of crops in the Central Valley.

Almonds rely on insects for 100% of their pollination requirements, and pollination is the first and most important step in the almond producing process. In mid-February, billions- yes billions!- of flowers open up on Almond trees around the Central Valley, each demanding at least one individual visit from a pollen-carrying bee. Pollination is a delicate and labor-intensive process- and for almonds, it is essential. In the early spring, almond orchards around the state turn a pinkish-white, and flower petals make orchards look like they've had a recent dusting of snow. Pollination of the world's largest crop of almonds requires a big workforce, so growers call in the big guns. Beekeepers from around the country migrate to California in mid-February to provide the workforce- over a million colonies of bees, adding up to billions of individuals- it's the largest assembly of honey bees in the world. In February and March, California literally buzzes.

If you look at beautiful photos of almond orchards in bloom, the sheer number of flowers is mind-boggling. So, when I couldn't get an immediate answer from google for the number of flowers on an almond tree, I decided to investigate a bit further. The following is based on representative numbers from sources that I consider to be reliable, but probably not very exact (links through to the sources if you want to investigate), so, don't take these figures to be exact, just to give us an indication of the job bees are expected to do for almonds. Average nut set on almond trees in California is around 7,300 nuts per tree. At around 124 trees per acre, that's 905,200 flowers that need to be pollinated per acre of orchard. In California there are 800,000 acres of almond orchards. Across California, that means 724,160,000,000 flowers (over seven hundred billion!) were successfully pollinated last year. This number doesn't include flowers that don't successfully develop into nuts, so is likely to be very conservative.

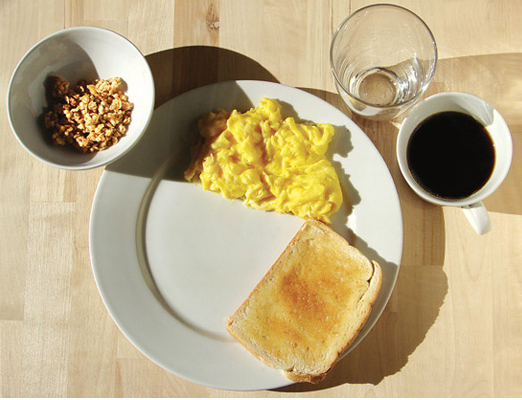

Bees are crucial, and they need to be looked after carefully. In 2009 Scientific American published these photos of a typical breakfast with and without the pollinating services of honey bees.

Almonds rely on insects for 100% of their pollination requirements, and pollination is the first and most important step in the almond producing process. In mid-February, billions- yes billions!- of flowers open up on Almond trees around the Central Valley, each demanding at least one individual visit from a pollen-carrying bee. Pollination is a delicate and labor-intensive process- and for almonds, it is essential. In the early spring, almond orchards around the state turn a pinkish-white, and flower petals make orchards look like they've had a recent dusting of snow. Pollination of the world's largest crop of almonds requires a big workforce, so growers call in the big guns. Beekeepers from around the country migrate to California in mid-February to provide the workforce- over a million colonies of bees, adding up to billions of individuals- it's the largest assembly of honey bees in the world. In February and March, California literally buzzes.

If you look at beautiful photos of almond orchards in bloom, the sheer number of flowers is mind-boggling. So, when I couldn't get an immediate answer from google for the number of flowers on an almond tree, I decided to investigate a bit further. The following is based on representative numbers from sources that I consider to be reliable, but probably not very exact (links through to the sources if you want to investigate), so, don't take these figures to be exact, just to give us an indication of the job bees are expected to do for almonds. Average nut set on almond trees in California is around 7,300 nuts per tree. At around 124 trees per acre, that's 905,200 flowers that need to be pollinated per acre of orchard. In California there are 800,000 acres of almond orchards. Across California, that means 724,160,000,000 flowers (over seven hundred billion!) were successfully pollinated last year. This number doesn't include flowers that don't successfully develop into nuts, so is likely to be very conservative.

Bees are crucial, and they need to be looked after carefully. In 2009 Scientific American published these photos of a typical breakfast with and without the pollinating services of honey bees.

Blue orchard bee. Photo from USDA.

Blue orchard bee. Photo from USDA. Seventy-five percent of crops rely on pollination from bees, and around the world this reliance upon honey bees in particular is being revealed as an Achilles heel for agriculture.

Something is causing honey bees to die, at alarming rates.

Eric Mussen, an apiculturalist at the University of California Cooperative Extension, says that a storm of dangerous elements may be to blame. Bacteria (such as American foul brood), Fungi (such as Nosema spp.), Viruses (there are 22 named RNA viruses that affect honey bees), and Parasites (such as varroa mite)- all can kill bees or cause them to become ill. Because of the social nature of the bee hive, bees living in a colony can pass these culprits along to other bees or larvae. Pesticides, even if they aren't directly sprayed on the bees, can be picked up by worker bees and can cause a decline in immune function- opening bees up to infections.

Something is causing honey bees to die, at alarming rates.

Eric Mussen, an apiculturalist at the University of California Cooperative Extension, says that a storm of dangerous elements may be to blame. Bacteria (such as American foul brood), Fungi (such as Nosema spp.), Viruses (there are 22 named RNA viruses that affect honey bees), and Parasites (such as varroa mite)- all can kill bees or cause them to become ill. Because of the social nature of the bee hive, bees living in a colony can pass these culprits along to other bees or larvae. Pesticides, even if they aren't directly sprayed on the bees, can be picked up by worker bees and can cause a decline in immune function- opening bees up to infections.

Both native and honey bees feeding on coyote brush flowers in October

Both native and honey bees feeding on coyote brush flowers in October Sustainability comes in many shapes and forms, but it is often hinged upon not over-exploiting, or relying too heavily, upon a single resource. In the case of pollination, sustainability means having a diversity of pollinators around a farm- not just honey bees, but native bees as well. So, like all good businesses, the crops that rely on pollination will need to diversify to ensure their returns. This diversity comes from the roughly 4,000 species of native bee that can be found in North America. Research has shown that native bees provide a LOT of pollinating services, increase the work ethic of the honey bees, and can even do a better job of pollinating than their Apis counterparts- with native bee pollinated flowers producing larger fruit.

In fact, if honey bees are unable to keep performing at their incredible rates, we will reply more on native bees to step in and provide the pollination services. This means providing the native bees, which don't live in hives and cannot be easily moved around like honey bees, with homes and alternate food sources. Like all animals, bees need to eat, and they need a place to call home. Areas of natural habitat and non-plowed land provide food sources for bees, to sustain them when crops aren't flowering, as well as places to build nests and lay eggs. In vast areas of intensive agriculture, where huge fields are only broken by weedy edges and irrigation ditches there is little space for native pollinators to feed and live, which means fewer workers when the crops need pollinating.

As UC Davis Professor Neal Williams describes it- this is the 'irony of intensive agriculture and pollination'.

The solution? Part of it is to plant field edges with hedgerows where bees can nest, and which provide food for both native and honey bees when crops aren't flowering. These hedgerows can also provide habitat for birds to nest, and for beneficial insects that prey upon pests. More on hedgerows and their impact on animals in future posts.

In fact, if honey bees are unable to keep performing at their incredible rates, we will reply more on native bees to step in and provide the pollination services. This means providing the native bees, which don't live in hives and cannot be easily moved around like honey bees, with homes and alternate food sources. Like all animals, bees need to eat, and they need a place to call home. Areas of natural habitat and non-plowed land provide food sources for bees, to sustain them when crops aren't flowering, as well as places to build nests and lay eggs. In vast areas of intensive agriculture, where huge fields are only broken by weedy edges and irrigation ditches there is little space for native pollinators to feed and live, which means fewer workers when the crops need pollinating.

As UC Davis Professor Neal Williams describes it- this is the 'irony of intensive agriculture and pollination'.

The solution? Part of it is to plant field edges with hedgerows where bees can nest, and which provide food for both native and honey bees when crops aren't flowering. These hedgerows can also provide habitat for birds to nest, and for beneficial insects that prey upon pests. More on hedgerows and their impact on animals in future posts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed