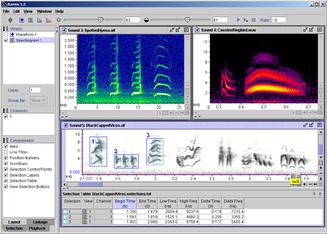

After a long summer... it's time to start looking at data!

This has been the longest field season I've ever sustained. It's been hot, muddy, dusty and dry. I've gotten my car stuck in the mud (but pushed it out unscathed), have scraped myself countless times on chicken wire, and have turned the bottoms of my field pants green from walking through tomato fields. But- it's been a great summer too! I've got (binders full of) data to sort through over the next couple of months- hopefully with some publications to come out of it all at the other end. There are also exciting collaborations with Audubon and PhD candidate Sacha Heath using our bird abundance data collected by Breanna Martinico, Ryan Bourbour, and Sam Lei, and the barn owl pellets to dissect for our owl diet study.

This summer's team of interns were really the ones that kept everything going. Breanna Martinico in particular who kept things organized and running smoothly whenever I was out of town. Ryan Bourbour, Erin Barry, Joshua Heasell, Brian Vu, Jeffery Haight and Sara Remmes were all dedicated and enthusiastic members of the summer #WildAg team, all willing to get their hands dirty and spend morning hours harvesting tomatoes or sorting through alfalfa samples. I'm extremely grateful to be working at UC Davis, where giving students the opportunity to experience research firsthand as interns is a teaching method.

Now that fieldwork is over, I'll have more time to think and write- so expect a lot more activity on this blog over the winter months. For now, below is a storify of images tweeted from the #WildAg experiment over the past couple of months (follow me on twitter @sara_kross for more photos and news stories about agriculture and wildlife!).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed